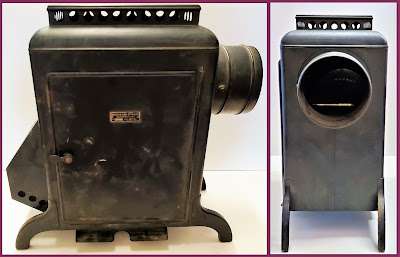

This artifact from the museum is a product of the Bausch and Lomb Company they called a “Home Balopticon”, one of their line of products of “Magic Lanterns”. This model has an indication of its patent Feb. 9 – 1915/ May 1- 1917, which gives us a date to work with for this artifact as late 1910s, possibly 1920s. What is a magic lantern? The early versions of these devices were invented in the 1600s, most likely by Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens, and projected images on moving pieces of glass by illuminating them by candlelight.

As technology changed, so did these devices, becoming a common form of entertainment and education in Europe by the 18th century. The first use of them in the United States is recorded as December 3, 1743 in Salem, Massachusetts and most likely incorporated the use of oil lamps. “Limelight” – created by a piece of limestone in burning gas until incandescent – was used in the 19th century, along with kerosene oil. Neither were very bright but accomplished the job with a greater degree of safety that they could be used in a wider capacity. Churches, schools, fraternal societies and even home/toy versions were introduced. They experienced a boom in popularity with electric illumination in the early 20th century, especially in America.

The Bausch & Lomb Company began in 1853 by German immigrant, John Jacob Bausch in Rochester, N.Y. He partnered with Henry Lomb, also an immigrant to the United States as a result of the German revolution of 1848. They greatly aided and advanced the field of optical technology, from rubber eyeglass frames of vulcanized rubber (revolutionary material at the time) to the first photographic lens in 1883, to the first producer of optical quality glass in the United States in 1912. Bausch & Lomb produced 40,000 pounds of glass during the 1910s, particularly for the United States government by supplying 65% of its needs in the form of binoculars, rifle scopes, telescopes and searchlights in World War I.

The Balopticon (combining “ba” from Bausch, “lo” from Lomb, “opti” from optical and “co” for company) was first produced in 1911. The 1917 Bausch & Lomb Optical Co. Projection Apparatus booklet describes the Home Balotpicon in this way:

“This Balopticon has been designed to meet the popular demand for a really efficient, but inexpensive instrument, for the projection of post cards, photographs and similar objects in the home, the small classroom and the Sunday school room….It is so simple in operating that any child can operate it, yet it far excels the ordinary post card projector in the quality of the picture produced, the illumination and its wide range of usefulness.”

The device operated by placing an object like a postcard on the bottom of the inside chamber, rather than in the wall like previous magic lantern devices – a bonus to those wanting to project a solid object like a coin or curios or wanted to avoid cutting up a book or magazine to display a portion of the paper. It also allowed for easier changing of items. An interior mirror brings the image into the correct left to right position when projected out the lens for the audience. It operated on 400-watt gas-filled Mazda lamps. Also, according to some sources, the interior chamber was also insulated with asbestos…but not in the company’s official apparatus booklet so maybe, but maybe not.

Like with any good product, there were add-ons that could also be purchased. A larger screen for classroom use could be purchased, lamps of higher voltage, and even the option of purchasing a carrying case. Of course, keeping it simple, you could be a standard or a combination model. Or even one recommended for English Departments that has a larger opening in the bottom of the dark interior chamber.

The version in the museum doesn’t appear to be a combination model, as it is missing the portion directly under the lens. This allowed for an aluminum screen and lantern slide equipment to be attached, with bellows and a front standard carrying a smaller achromatic projection lens in a spiral focusing mount, producing pictures from slides rather than opaque objects. It’s also missing its cord to be plugged in so there won’t be any demonstrations in the near future it seems.

So how much would this precursor to an overhead projector cost you? In this 1917 booklet, the models range from $35, $45, and $84. That roughly would be in today’s money $701.08, $901.39, and $1,682.59.